Rosebud

On March 17, 1941, just a couple of days after the world premiere of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, novelist/movie critic John O’Hara (often referred to as “The Rodney Dangerfield of American literature”) wrote a review of the movie for Newsweek Magazine. O’Hara began his review in the following manner:

It is [with] exceeding regret that your faithful bystander reports that he has just seen a picture which he thinks must be the best picture he ever saw.

With no less regret, he reports that he has just seen the best actor in the history of acting.

Name of picture: Citizen Kane.

Name of actor: Orson Welles.

Reason for regret: you, my dear, may never see the picture.

O’Hara’s reasons for the last line were multitudinous; it said as much about Hollywood’s feelings for the then 26-year old Welles, as it did about the Hollywood establishment itself.

[George] Orson Welles (1915-1985) claimed that the first words he ever heard while still in the cradle came from Dr. Maurice Bernstein (the Welles’ family physician), who proclaimed the infant a prodigy, “a genius in the making.” It turned out, of course, to be true. (Years later, Welles would immortalize the good doctor by naming John Foster Kane’s business manager “Mr. Bernstein” in Citizen Kane. (The character, whose first name was never mentioned, was played by the venerable character actor Everett Sloane.)

Julius Caesar with Orson Welles and Martin Gabel as Cassius.

By his mid-teens, Orson Welles had convinced the manager of Dublin’s Gate Theatre that he was an important American actor, and starred in several of that legendary theatre’s productions. After about a year, he returned to America before his 19th birthday and created both the “Mercury Theatre on the Air” on radio and Broadway’s “Mercury Theatre,” the former of which scared much of the East Coast with his Halloween broadcast of H.G. Welles’ (no relation) “War of the Worlds.” Welles also became radio’s “The Shadow,” and went on to both produce and star in a modern-dress version of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (as an anti-Fascist, anti-Mussolini drama); it turned out to be one of the 20th century’s most compelling versions of a Shakespearean play. He also produced and starred in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes and Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, among many, many others. And mind you, by this time he was barely twenty.

Working alongside his producer, future Oscar winner John Houseman, Welle’s Mercury Theater even had its own “Declaration of Principles,” - a statement which vowed that the company would cater to patrons “on a voyage of discovery in the theater,” who wanted to see “classical plays excitingly produced.” Fans of Citizen Kane will recognize in this the “Declaration of Principles” that John Foster Kane created for his first newspaper . . .

Not surprisingly, Hollywood came courting. What was surprising, were the terms that RKO Studios offered the younger-than-young Welles: $150,000.00 ($2.8 million in today’s money) for each of two films of his choice, for which he could act as producer, writer, director and screen star, as well as having virtual complete control of the final film Prior to this earth-shattering contract, the studio chiefs maintained nearly complete control over a film’s destiny, including its script, casting, production budgets, assignment of technical staff, and the editing of the footage into a final print.

Nonetheless, no one, save Charlie Chaplin (who was using his own money) had ever received such an offer; heretofore, writers wrote, directors directed, producers produced and actors acted. But there was just something about Orson Welles. Even before Welles and his Mercury Theatre troupe detrained at the Pasadena Station, people in Hollywood were dubious, envious and wickedly jealous of the boy genius. As one biographer would note, “Welles radiated the physical presence of a movie idol long before he set foot in Hollywood.” Resentment and distrust were compounded when Welles arrived in Hollywood proper, sporting a beard [left over from his aborted production of Five Kings – an ambitious compilation of five of Shakespeare’s plays about British monarchs that Welles still hoped to produce after he completed a stint in Hollywood] . . . the beard served to alienate some . . . and amuse others. According to an article in The Hollywood Reporter, “Errol Flynn sent Welles the perfect Christmas gift for a whiskered actor: a ham with a beard attached to it.”

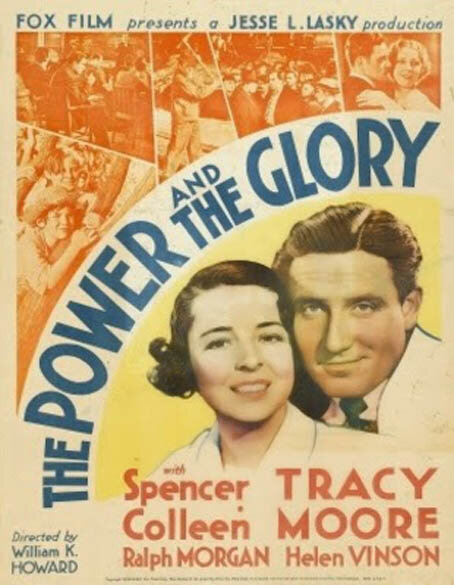

Upon his arrival at RKO studios, Welles - accompanied by his future cinematographer Gregg Toland - went over virtually every square inch of the lot, with Welles drinking in every facet of film-making. When asked by the press what he thought about the studio, Welles likened it to “the best electric train set any kid ever had!” At night, he began contemplating his first film . . . but what would it be? His first inclination was an adaptation of British writer Eric Ambler’s Journey into Fear (which Welles would make right after “Citizen Kane.”) The studio turned him down flat: Welles’ proposed budget for Journey was around $1 million; his contract permitted no more than $500k per picture. Welles countered with Nicolas Blake’s espionage thriller The Smiler With a Knife. This too was rejected due to cost. In the meantime, Welles also watched plenty of films plenty of times. These included John Ford’s Stage Coach, Charles Chaplin’s City Lights and a minor 1933 film, The Power and the Glory, whose screen writer, Preston Sturges, would become the next great writer/director/producer. This picture, which starred a young rising Spencer Tracy and former silent superstar Colleen Moore, told the story of a man’s life . . . beginning with his funeral and then working backwards to his extreme youth. Welles loved the “life-told-in-reverse” concept; it eventually became the storytelling lynchpin of Citizen Kane.

Screen writer Herman Mankiewicz (whose grandson Ben is a host on Turner Classic Movies), who was recovering from a severely broken leg was sent away from Hollywood with John Houseman and a secretary to begin work on a screenplay originally entitled “American,” then “John Citizen, U.S.A.” Mank officially went on the RKO payroll ($1,000 per week) on February 19, 1940. While Mank wrote and Houseman kept the isolated screenwriter from drinking, Welles was back in Hollywood doing his initial pre-production work with cinematographer Toland. What Welles and Toland came up with was a work of sheer genius. Many of their scenes would be shot with ceilings. For the most part, no one used ceilings . . . that’s where lights are hung. So instead, they shot upwards, often digging holes in the floor for the camera to be encased. They were able to film what appeared to be immense gatherings, while through ingenious movie magic, there were actually only had 15-20 people in the scene. The most famous of these are shots of Kane’s campaign speech . . . which contain only a few players in any individual shot; the overall impact is one of thousands of people appearing in a whirlwind of action. The ‘audience’ in the meeting hall is actually a matte painting, pricked with holes so light would shine through and give the illusion of motion to the ‘crowd.’”

Then too, there is the brilliant scene where Kane’s 2nd wife, Susan Alexander (played by Dorothy Comingore) is about to make her operatic debut: the screen seems filled with mobs of frenzied people from the staff and company of the opera production; the impact is achieved by carefully plotting the rushing of actors across the stage at five different distances from the camera – some only a few feet from the lens, blacking out the scene. What seems like hundreds of people filling the frame is no more than twenty; the resulting visual impact of the intricately choreographed small groups of actors provided a far more stylized look to Citizen Kane than would more traditional surgings of teeming mobs. Susan appears to be performing before a full house; in reality, there is no one in front of her. By shooting from behind the diva into the lights, the mind of the cinema-goers fill in the house through suggestion . . . thus saving tens of thousands of dollars.

Deep Focus Photography at it’s Very Best

But the most fascinating thing Welles and Toland did in Citizen Kane was to employ a cinematic technique called “deep focus photography,” in which front, mid-range and back set could be filmed clearly all at the same time. Generally, when someone is right in front of the camera and speaking to someone at a distance, the moment the person being spoken to responds, they become the clear-eyed focus of the camera while the one who originally spoke becomes blurred. In deep-focus, everyone remains in focus. In fact, there is one scene in Citizen Kane which, although adding little to the story, is used in order to show off what Toland and Welles were doing. This is the scene where Welles is about to sign over his corporate ownership rights to the bank. Kane (Welles) gets up from the table where Mr. Bernstein and their longtime banker, Mr. Thatcher (played by George Coulouris) are seated. Kane walks and talks until he reaches the back of the room . . . which is far more distant that at first it appears to be . . . and then returns to the table. The only reason for this set-up is to show the magic of deep-focus. By far, the greatest - and most difficult - of all deep-focus shots came when Kane broke into his wife Susan’s bedroom soon after she had tried to commit suicide. Even the still shows the door, Kane and the bottle of poison in perfect focus . . . a prodigious feat of cinematography.

This use of deep-focus was as much a product of good timing as anything. From Toland’s point of view, Citizen Kane was not only well-timed artistically, but technically as well. New developments in both lighting and film – in particular the release of Kodak’s new Super XX black-and-white film stock in 1938 – opened vast new horizons for cinematographers, allowing them to shoot with less light and achieve greater contrast and depth to the image. And although the movie-goer does not necessarily understand what they are seeing, it nonetheless leaves a lasting impression.

In addition to writing, directing and rehearsing his cast, Welles was also the star of the film, which meant often having to be in make-up by 3:00 in the morning. During the making of Citizen Kane, the makeup department created a total of seventy-two assorted face pieces for Kane – among them sixteen different chins alone – as well as ears, cheeks, jowls, hairlines, and eye pouches . . . aging him from twenty-five to seventy-eight. In one of the film’s most famous scenes - showing the dissolution of Kane’s marriage to Emily across the breakfast table - Welles decided that it would be best to film the scenes in reverse. He reasoned that it take far less time to strip away a layer of makeup and wigs - going from oldest to youngest - than doing the opposite. As such, Welles and Ruth Warrick were able to accomplish this vignette in a single day’s shoot. (n.b.: Welles always wore a prosthetic nose whenever he was on-screen or on-stage; he felt that his own was too small for his face.)

One question the public asked when they first saw Citizen Kane was where Welles had found all the great unknown actors who filled the various major roles: people like Joseph Cotten (Jed Leland), Agnes Morehead (Mary Kane), Ruth Warrick (Emily Norton Kane), George Coulouris (Walter Parks Thatcher), Ray Collins (“Boss” James Gettys), the aforementioned Everett Sloane (Mr. Bernstein) and Paul Stewart (Raymond, Kane’s butler) . . . all of whom would go on to long careers in Hollywood. The answer is simple: Welles merely moved his Mercury Theatre players out west to RKO.

Charles Foster Kane and Susan Alexander

Herman Mankiewicz and John Houseman originally thought about modeling their main character on millionaire inventor/pilot/filmmaker Howard Hughes, but soon settled on publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst. Unlike Hughes, who was too young and not exciting enough in real life, Hearst presented a character and appetites were truly larger than life. The public never had to be told that Charles Foster Kane was based mostly on Hearst, nor that Kane’s other-worldly estate “Xanadu” was undoubtedly based on Hearst’s castle (which the magnate simply referred to as “the ranch”) in San Simeon. Did it then follow that Susan Alexander, Kane’s second wife whom he tried desperately to turn into a operatic diva, was modeled after Hearst’s longtime mistress, movie actress and former Ziegfeld Girl Marion Davies? Perhaps yes, perhaps no. Personally, I have always seen Susan as an amalgam of at least 3 famous (or infamous) 20th century courtesans:

Ganna Walska (1887-1984), who was married to publishing heir Harold McCormick (fourth of her six husbands), got him to finance an opera career for her; problem was, she couldn’t sing a lick;

Kodak chairman Jules Brulatour (who also founded Universal Pictures) funded his 2nd wife Dorothy Gibson’s film career, and then his 3rd wife Hope Hampton’s aspirations in grand opera; Hampton, like the fictional Susan Alexander, did not fare very well. Hampton married several other multi-millionaires and became known as ““The Duchess of Park Avenue”

(A future “Tales from Hollywood & Vine, tentatively entitled Who Was Susan Alexander? is already being researched and outlined. It should be ready for posting within the next 8 weeks.)

It goes without saying that Hearst was furious with both RKO in general and Orson Welles in particular. He decided that if Welles and RKO released the picture, he would destroy them. No one, he bellowed, had the right to satirize, demean or make a fool of either him or his beloved Marion. At one point, Hearst attempted to buy up the rights to Citizen Kane with the idea of destroying the master print. Welles threated to sue RKO; RKO told Hearst to take a hike.

Welles did, however, relent on one scene in which he had Susan Alexander, Kane’s increasingly alcoholic second wife have an affair with another man. Hearst was livid; he adored Marion, and even though he never divorced his wife to marry Miss Davies, he refused to have anyone suggest - even on film - that Marion was anything but faithful to the man she frequently and lovingly referred to as “Old Droopy Drawers.” This is not to say that Marion was a vestal virgin. Back in 1924, word got around Hollywood that Marion was carrying on with Charlie Chaplin. On one occasion, when Charlie and a bunch of Hollywood bigshots went out on Hearst’s yacht, the Oneida, Hearst caught Chaplin and Miss Davies canoodling in the latter’s cabin. Chaplin escaped, went out on deck and hid under the tarp of a life saving boat. Hearst, armed with a pistol chased Chaplin and fired at a man standing in front of him. It turned out that the man he hit was not Charlie Chaplin, but rather famed producer/director Thomas Ince, who actually looked quite a bit like the silent comedian. Ince died several days later at his Beverly Hills home from his gunshot wound. Louella Parsons, the Hearst writer covering Ince’s death, reported that the director had died from a heart attack. For her loyalty to Hearst, Parsons was rewarded with a lifetime contract and eventually became Hollywood’s most fearsome gossip columnist. And as long as W.R. Hearst lived, Parsons would do his bidding . . . up to and including panning any picture produced by RKO or Orson Welles. This had a lot to do with the financial failure of Citizen Kane.

In the end, Charles Foster Kane died alone, surrounded by his art and at a loss for friends or mourners. As the collectibles and detritus of an opulent life are consigned to a furnace, the one question asked (by a young, uncredited actor named Alan Ladd) is what did his dying word - “Rosebud” mean? We discover during the final frame that it was the name emblazoned on a cheap sled he had been given as a child. So perhaps it was an expression of longing for his age of innocence - the last time he had felt truly happy or secure. So far as the story of Charles Foster Kane goes, that works about as well as anything. However, in the backstory that is Citizen Kane, “Rosebud” does have a purpose and a meaning. According to those who knew Hearsts and Davies well “Rosebud” was Hearst's term of endearment for Davies’ pudenda, to employ medical terminology, or “honeypot” to a bit raunchier.

Today, Citizen Kane is largely considered to be the greatest film ever made. And although it failed at the box office and received less than stellar distribution in its first year on the circuit, it did receive 8 Academy Award nominations, won for best original screenplay (Welles/Mankiewicz), and earned the praise of many, many respected critics, including John O’Hara, whose pithy remarks opened up this post.

But Welles, Hollywood last spectacular wunderkind wound up having the last laugh. Despite a 40-year career as an actor, writer director and producer, he would have many ups-and-downs, gain a ton of weight and spend much of his time raising funds for his next picture. But throughout it all, that initial contract with RKI remained a living, breathing entity. When, in 1986 Turner Entertainment Company, which had obtained the home video rights to Citizen Kane in 1986, announced with much fanfare on January 29, 1989 its plans to colorize Welles’ masterpiece, there was an immediate backlash with the Welles estate and Directors Guild of America threatening legal action. Turns out, the contract which Welles had signed with RKO back when he was no more than a youngster, gave him - and his heirs - the rights to the film. As such, no changes could be made without the express written consent of Welles, his children, grandchildren or assignees.

Rosebud!

Copyright©2021 Kurt F. Stone