Hollywoodland: Bringing Zukor and Goldwyn, Cohen, Mayer, Fox, Warner and Laemmle Back Home

September 25, 2021 was a very special day. For not only did it fall on the Jewish Sabbath (shabat) in the midst of Hag Sukkot, (the Fall harvest festival), but, after more than 17 years of planning, fundraising and meticulous craftmanship the long-awaited Academy Museum of Motion Pictures held its grand opening. The mammoth project was, to a great extent, the brainchild of Sid Ganis, a former president of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) and an award-winning producer of, among other films, Akeelah and the Bee. I’ve known Sid and his wife Nancy for many years . . . ever since I officiated at the funerals of Sid’s parents in South Florida. The Academy Museum, housed in a magnificent structure located at 6067 Wilshire Blvd, is well-known to native Angelinos and Hollywood Brats alike as “The old May Company building.” It is but a hop, skip and jump from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the La Brea (Spanish for “tar”) Pits, billed as “A paleontological gateway back to the Ice Age, right in the heart of L.A.”

The Academy Museum’s opening exhibitions included, in the words of museum director Bill Kramer, “ . . . moments devoted to The Wizard of Oz, Citizen Kane, Spike Lee, Hayao Miyazaki, costume design, visual effects, sound design, pre-cinematic storytelling and so much more.” Early visitors widely praised the museum for its design, the quality of its exhibits and its vast assortment of cinematic memorabilia. However, before too long, a question began growing among patrons and visitors: “What happened to the Jews?” For it turned out that a museum devoted to an industry largely birthed by the likes of Samuel Goldwyn (Szmuel Gelbfisz), Adolph Zukor (Paramount) Fox’s William Fox (Wilhelm Fuchs), Carl Laemlle (Universal) the brothers Warner and Harry and Jack Cohen (Columbia) were all AWOL. And to make matters even more confusing, the overwhelming role played by Jews in the creation of the Hollywood film industry was being housed in a structure whose major financial backers were themselves Jewish: media mogul Haim Sabin and producer/director Steven Spielberg.

Before too long, articles began appearing in Jewish papers like The Algemeiner, and The Forward, not to mention the Hollywood Reporter, Rolling Stone and eventually the New York Times. In their own way, each writer asked the same exact question: What became of the Jews? Why weren’t they included in the museum? One writer noted “ . . . scant mention of Jewish trailblazers,” with the exception of “Sunset Boulevard” director Billy Wilder, and that “One of the six Oscars won by Wilder is displayed with a small placard stating that he fled Nazi Germany due to his religion.”

My mostly-Jewish film students at Florida Atlantic University (which bills me, their instructor, as “The University’s resident ‘Hollywood Brat’”) – began asking me to explain the museum’s glaring oversight, and then wanting to know what “You, Dr. Stone, are going to do about it.” Truth to tell, I had no answer to their first question, but promised to look into it and see what I could do . . .

Then, on January 18, 2022, my phone rang. The name on the I.D. was that of my friend Sid Ganis. I naturally assumed that the call dealt with a project we were working on - one which had virtually nothing to do with the museum. But to my amazement, there he was, on the line, asking me if I would be interested in becoming part of an advisory panel whose purpose was to create a permanent exhibit on the role that Jews played in the creation of the film industry. It took me a nanosecond to say “Yes!” Within five minutes, I was on the phone speaking to the museum’s director, Bill Kramer. In all honesty, my first thought was how proud our recently-deceased mother (“Madame”) would be to know that her youngest had received the invite.

And so the work began . . .

Jesse Lasky, Adolph Zukor, Sam Goldwyn and Cecil B.De Mille

To “Hollywood Brats” and historians of Hollywood in general (which was originally pronounced “holly-WOOD”), its Jewish involvement is a given. Prior to the West Coast, the majority of films were made in New York City . . . except for Westerns, which were made almost exclusively in New Jersey. That all changed, in 1913-14 when the Hungarian Jewish furrier Adolph Zukor, along with the San Franciso-born vaudevillian Jesse Lasky, Lasky’s brother-in-law the Hungarian-born glove salesman Szmuel Gelbfisz (Sam Goldwyn) and actor/playwright Cecile B. DeMille, the son of a Jewish-born Brit named Helena Beatrice Samuel, spent a minor fortune to purchase the rights to a Broadway play called “The Squaw Man” for the sole purpose of making a photoplay out West. When the tortuous heat of Arizona proved to be totally inhospitable (their film melted), they pushed on to the Pacific Coast, rented a barn at the southeast corner of Selma and Vine Streets, and shot their picture. It cost about $15,000 (about $245,000 in 2022) to make, and earned the partners nearly a quarter million dollars - just under $6,000,000 in today’s dollars. (The picture was so successful that its director, Cecile B. DeMille, remade it 2 more times: a second silent version 1918 and a talkie version in 1931).

1914’s The Squaw Man put Hollywood on the map.

As Jewish producers began creating their nascent studios in and around Hollywood, they hired Jewish directors - mostly from Europe - and began making stars out of Jewish actors and actresses. But hardly anyone in the growing movie-going public had the slightest idea that directors like Erich von Stroheim, Ernst Lubitsch, Josef von Sternberg or Lewis Milestone; superstars such as Sarah Bernhardt (Henriette-Rosine Bernard), “Broncho Billy” Anderson (Maxwell Aronson) Theda Bara (Theodosia Goodman), Alla Nazimova (Miriam Leventon), Douglas Fairbanks (Douglas Elton Ulman) or Edward G. Robinson (Emanuel Goldenberg) were Jewish as well.

And then, moving into the early talkie era, Jewish producers made stars out of such Jewish actors (again, whom most of the public hadn’t the slightest idea were Jewish) like Paul Muni (Meshilem Meier Weisenfreund), Ricardo Cortez (Jacob Krantz), Sylvia Sidney (Sophia Kosow), Al Jolson (Asa Yoelson), Peter Lorre (László Lowenstein), Bert Lahr (Irving Lahrheim) and Ed Wynn (Isaiah Edwin Leopold) to name but a few.

When it came to producing films with Jewish content, the Hollywood moguls showed distinct discomfort. While it is true that the cash-strapped brothers’ Warner released one of early Hollywood’s most overtly Jewish-themed films (1927’s The Jazz Singer starring the Lithuanian-born Al Jolson, who, in real life was the son of a cantor) many believe that the reason they added sound (“You ain’t heard nothing yet!”) was to insure its profitability all across the country . . . and not just in New York, Chicago or Hollywood. (It should be noted that the Warners’ casting office chose the Swedish-born Warner Oland [nee Johan Verner Öhlunda, a future Charlie Chan] to play the part of Jolson’s father the Cantor).

Two years later, Warner Brothers released Disraeli, starring the distinguished British actor Mr. George Arliss (who had made a career of playing the late Jewish-born P.M. in both London’s West End, on Broadway, and in a 1921 silent version); one would have had to listen very closely to discover that the lead character was Jewish. In 1932, the 30 year-old David O. Selznick teamed up with Pandro Berman at RKO to release the ironically-named (and now largely forgotten) Symphony of Six Million, based on a a story by the one of that era’s most popular writers, the Jewish-born Fannie Hurst. Starring Ricardo Cortez (Jacob Krantz) as the Lower-East Side-born Dr. Felix “Felixel” Klauber, the film told the story of a young Jewish physician who rose from his humble Lower East Side roots to the top of his profession and how the social costs of losing his connection with his community, his family and the craft of healing led to a crisis of conscience. The film never mentions the word "Jew" or specifically points out that the characters are indeed Jewish. But it does include Jewish prayers, such as the Shema, recited in Hebrew, and incorporates a Pidyon Ha-Ben, the Jewish ritual Redemption of the First Born.

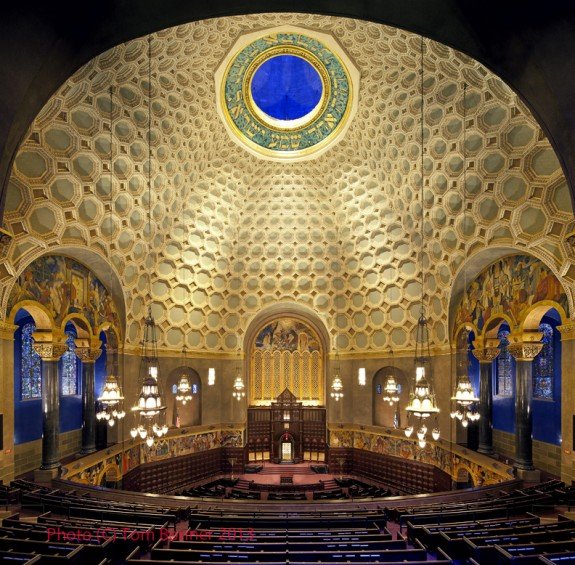

The Wilshire Blvd. Synagogue Sanctuary

Two additional Jewish-themed films of the 1930s: Universal Pictures’ Counsellor at Law (1933), starring the unbelievably miscast John Barrymore as Jewish attorney George Simon. The film was adapted from a play by Elmer Rice (Reizenstein), produced by Carl Laemmle, Jr., and directed by William Wyler (a cousin of Universal’s founder Carl Laemmle). Then, in 1937 Warner Brothers’ classic The Life of Emile Zola starring two distinguished actors from the Yiddish theater, Paul Muni as the writer Zola and Joseph Schildkraut as the French Captain Alfred Dreyfus (both of whom received Oscars for their performances), who was falsely accused of giving over French military information to the Germans. Based on one of history’s most notorious anti-Semitic conspiracies, nowhere in the script does one find the word “Jew” or “Jewish.” When asked about this in later years, Jack Warner said that it was done on purpose in order to make the picture’s “message” more universal. For their efforts, Jack Warner did walk away with the Best Picture Award for 1937.

Although the original moguls were both uncomfortable and intensely private when it came to being Jewish, they did build one of the most opulent Reform Synagogues in the world: the Wilshire Blvd Temple, located 24 blocks away from where the new Academy Museum sits. Completed at a cost of $1.5 million in 1929, the Temple was built largely through the donations of Louis B. Mayer, Irving Thalberg, and the Warner brothers. In keeping with its Hollywood roots, the sanctuary’s magnificent murals were created by studio artist Hugo Ballin.

The “other” synagogue in Hollywood, Temple Israel on Hollywood Blvd., was founded in 1926 by seven men, five of whom were prominent in the film industry, including Sol M. Wurtzel, Isadore Bernstein, and Edward Laemmle. From the time of its founding, the temple was well-known for its “Midnight Show,” a series of fundraisers which over the years saw such Jewish and non-Jewish stars as Eddie Cantor, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland and Lena Horne headline on behalf of the Temple.

In an article written for the March 21 , 2022 edition of The Hollywood Reporter Bill Kramer, director and president of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures and Jonathan Greenblatt, the CEO of ADL (Anti-Defamation League) wrote a front-page essay noting the absence of any reference - let alone exhibit - dealing with the immigrant Jewish experience as it related to the creation of Hollywood. As they noted, throughout the industry and among museum stakeholders, a single question was being repeatedly asked: “Where are the Jews?”

As it turns out, answering that question was not nearly as important as doing something about it. In their article, Kramer and Greenblatt noted that when the museum opened this past September, there was “ . . . a two-month screening and panel series on Viennese émigrés, many of whom were Jewish, who helped to define the classical Hollywood era, including Max Steiner, Billy Wilder, and Hedy Lamarr.” After numerous discussions and a great deal of what the authors referred to as “self-reflection” (which is something as deeply Jewish as Manishewitz, kvetching und kvelling), it was decided to create a permanent exhibit on this utterly crucial aspect of Hollywood history. The working title for the exhibit is “Hollywoodland,” named after the original sign adorning the hills above my home town. (First erected in 1923, the sign was meant to serve as an advertisement for a 640-acre real-estate development which never came to fruition due to the Stock Market Crash of 1929; the last 4 letters would be removed in 1949, which happens to be the year of my birth.)

Again, the reason or reasons why the Academy Museum opened without a permanent exhibit dedicated to the role immigrant Jews played in creating one of the most vibrant industries on the planet, really isn’t that important . . . and most likely unknowable. Perhaps it lay in the genomic make-up of the founders; being Jewish but neither comfortably nor obviously so. Then too, most of them had fled the anti-Semitism of Central and Eastern Europe and wanted nothing so much as to become 100% American. That they entered the world of nickelodeons, kaleidoscopes and celluloid isn’t, when stops to think about it, all that surprising. After all, this was a brand new endeavor; one which had few if any historic barriers or prejudices at its core. Then too, coming from such endeavors as gloves, coats, dresses and small dry goods stores, the future moguls possessed a collective innate sense of future trends and fashions . . . a marvelous asset for the making of motion pictures for the fickle masses. Three examples: Max Aaronson (Broncho Billy) foresaw the Western Film craze long before Tom Mix and William S. Hart arrived on the scene; Wilhelm Fuchs (William Fox) saw a future fortune to be made in the making of films centering around “vamps” before anyone else, and made Theda Bara, the daughter of a Jewish tailor, a star of international import within less than a year; Universal’s “Uncle Carl” Laemmle understood that the public would be far more excited about going to see movies over and over again when they knew (or thought they did) the names of their favorite stars as opposed to merely their nicknames such as "The Girl With the Curls” (Mary Pickford); "The Dimpled Darling” (Maurice Costello) or "The Biograph Girl” (Florence Lawrence).

The Academy Museum board, its officers, advisors and curators are looking to create and finish the “Hollywoodland” project within a year. I for one am terribly proud to play a role (small though it might turn out to be), and anxiously await the day when Meyer and Goldwyn, Zukor, Cohen, Warner and Laemmle can finally receive the tribute they so richly deserve.

Copyright©2022 Kurt F. Stone