Behind the Silver Screen: The Making of Chaplin's "The Great Dictator"

Quite apart from any particular merits of the film, The Great Dictator remains an unparalleled phenomenon, an epic incident in the history of mankind. The greatest clown and best-loved personality of his age directly challenged the man who had instigated more evil and human misery than any other in modern – if not all of human – history.

There was, to begin with, something uncanny in the resemblance between Chaplin and Hitler, representing opposite poles of humanity. And of course the fact that they had been born but 5 days apart in April, 1889. On April 21, 1939, a year and a half before the release of The Great Dictator, an unsigned article in the Spectator noted:

Providence was in an ironical mood when, fifty years ago, this week, it was ordained that Charles Chaplin and Adolf Hitler should make their entry into the world within four days of each other . . . Each in his own way has expressed the ideas, sentiments, aspirations of the millions of struggling citizens ground between the upper and the lower millstone of society; the date of their birth and the identical little moustache (grotesque intentionally in Mr. Chaplin) they well might have been fixed by nature to betray the common origin of their genius. For genius each of them undeniably possesses. Each has mirrored the same reality – the predicament of the ‘little man’ in modern society. Each is a distorting mirror, the one for good, the other for untold evil. In Chaplin the little man is a clown, timid, incompetent, infinitely resourceful yet bewildered by a world that has no place for him. The apple he bites has a worm in it; his trousers, remnants of gentility, trip him up; his cane pretends to a dignity his position is far from justifying; when he pulls a lever it is the wrong one and disaster follows. He is a heroic figure, but heroic only in the patience and resource with which he receives the blows that fall upon his bowler. In his actions and loves he emulates the angels. But in Herr Hitler the angel has become a devil. The soleless boots have become; the shapeless trousers, riding breeches, the cane, a riding crop; the bowler, a forage Reitstieffeln cap. The Tramp has become a storm trooper; only the moustache is the same.

There were even those who believed that Hitler had at first adopted the moustache in a deliberate attempt to suggest a resemblance to the man who had attracted so much love and loyalty in the world.

The famous Jewish short story writer Konrad Bercovici a close friend of Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, brought a plagiarism suit against Chaplin, claiming that he had first proposed that Chaplin should play Hitler in the mid-1930s. The case was settled, with Chaplin paying Konrad Bercovici $95,000 in 1947. In his autobiography, Chaplin insisted that he had been the sole writer of the movie's script. He came to a settlement, though, because of his "unpopularity in the States at that moment and being under such court pressure, [he] was terrified, not knowing what to expect next."

Bercovici was represented in his plagiarism suit by attorney Louis Nizer . In his book, "My Life in Court," Nizer goes into detail about Bercovici v. Chaplin: "The claim was that Chaplin had approached Bercovici to produce one of his gypsy stories as a motion picture and in the course of those friendly negotiations Bercovici gave him an outline of "The Great Dictator" story about a barber who looks like Hitler and is confused with him. Chaplin denied ever having negotiated for the gypsy story and also denied the rest of the claim...One day, upon my continuous inquiry, Bercovici suddenly had a flash of memory. He recalled that he had met Chaplin in a theater in Hollywood and that Chaplin had pointed out a Russian baritone in the audience whom he thought might play the leading role in the gypsy story. Bercovici believed that they spoke to the singer that evening and that he might possibly be a witness." Nizer tracked down Kushnevitz, the Russian baritone at issue: "He [Kushnevitz] recalled the incident vividly, for this, as he put it, was one of the great moments in his life - the possibility that he would star in a Chaplin picture. Chaplin had called him down the aisle of the theater and had given him his private telephone number. He pulled out a little black book from his back pocket and he still had the number written in it. He was a perfect witness in view of Chaplin's denial of any interest in Bercovici's gypsy story."

A good many newspaper cartoonists, notably David Low, might equally have claimed the idea as their own; after all, it was inevitable. Much later Chaplin admitted, ‘Had I known of the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made The Great Dictator; I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis. Hitler, true, turned out to be no laughing matter; but there was nothing light-hearted in Chaplin’s deeper intentions in making the film. He suffered very real and acute pain and revulsion at the horrors and omens of world politics in the 1930s. In a 1931 diatribe against the myth of patriotism, he foresaw with dread another war. A Far East tour he undertook in the mid-1930s had made him more alert than most to the perils of the so-called “Marco Polo Bridge Incident” of July 1937 and the escalation of the Sino-Japanese conflict. Also known as the “Lugou Bridge Incident,” or the “July 7 Incident,” it was a battle between the Republic of China’s National Revolutionary Army and the Imperial Japanese Army, often used as the marker for the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, which occurred between 1937 and 1945.

Chaplin was no less disturbed by events in Spain. In April 1938 the French film magazine Cinémonde published a translation of a remarkable short story by Chaplin himself, entitled “Rhythme.” It describes the execution of a Spanish loyalist, a popular humorous writer. The officer in charge of the firing squad was formerly a friend of the condemned man; ‘their divergent views were then friendly, but they had finally provoked the unhappiness and disruption of the whole of Spain.’ Both the officer and the six men of the firing squad privately hope that a reprieve may still come. Finally, though, the officer must give the rhythmic orders: ‘Attention! . . . Shoulder arms! . . . Present arms! . . . Fire!’ the officer gives the first three orders. Hurried footsteps are heard: all realize that it is the reprieve. The officer calls out ‘Stop!’ to his firing squad, but,

Six men each held a gun. Six men had been trained through rhythm. Six men, hearing the shout ‘Stop!’ fired.

The story at once embodies those fears of seeing men turned into machines which Chaplin had expressed in Modern Times (8), and looks forward to some grim, ironic gags in The Great Dictator.

There is more evidence of Chaplin’s feelings about Spain in a poem which he scribbled in a folio notebook among some memos on the development of Regency, presumably in the winter of 1936-37. The poem was quite clearly never meant for publication, or even for other eyes. It was a private attempt to express his sentiments.

To a dead Loyalist soldier

On the battlefields of Spain

Prone, mangled form,

Your silence speaks your deathless cause,

Of freedom’s dauntless march.

Though treachery befell you on this day

And built its barricades of fear and hate

Triumphant death has cleared the way

Beyond the scrambling of human life

Beyond the pale of imprisoning spears

To let you pass.

There was, he said euphemistically, ‘a good deal of bad behavior in the world’. Feeling as deeply as he did, he felt impelled to do whatever he could to correct it, or at least to focus attention upon it. His only weapon, as he knew, was comedy. Of course, he had attacked war with comedy in 1918, with his scathing satire Shoulder Arms (that’s Charlie and brother Syd on his right below), in which he had also played a soldier who is mistaken for leader of the Huns . . . except that in this case it was all a dream.

In the latter part of the 1930s Chaplin was very friendly with the director King Vidor and his family, and it was through the Vidors, sometime in 1938, that he met Tim Durant. Like Harry Crocker who, for many years, was Chaplin’s personal assistant, Durant was a tall, good-looking patrician, university-educated young man: Chaplin seemed to have a penchant for this type among his friends and assistants. Durant had the added merits of being sympathetic, amusing, discreet, and very good at tennis. Through Durant he was introduced into the society of Pebble Beach and Carmel, one hundred miles south of San Francisco. Chaplin called Pebble Beach ‘the abode of lost souls.’ He was fascinated, charmed and attracted by the collection of California millionaires who still made their homes there, and no less by the abandoned mansions that now lay in decay. The more Bohemian colony at nearby Carmel, a section of coast much favored by artists and writers, had a different but potent attraction. He was especially pleased by his meetings there with the famous California poet Robinson Jeffers, who coined the term “inhumanism,” the belief that mankind is too self-centered and too indifferent to the "astonishing beauty of things."

Tim Durant remembered that at first Chaplin was reluctant to become involved with the Pebble Beach set:

I knew a girl who was married to one of the Crockers in San Francisco, and she heard I was there and called me up and asked me to come over for dinner and bring Charlie. But Charlie said to me, ‘Listen, Tim, I don’t want to get into this group at all . . .’ I said, ‘Look, Charlie, will you do this just as a personal favour – I don’t ask you to do anything. Will you just go over and have dinner with them, and we can say honestly that we have to get back and do some work, and you can leave immediately.’

He said, ‘All right, Tim; but get me out of there, remember; don’t let me spend the evening there.’

So we went over there. We walked in and everybody congregated around him, you know, and he was a hero. He had an audience, and he couldn’t leave – wanted to stay until three o’clock in the morning. After that he wanted to go out every night, because they accepted him and he entertained them, and we went out all the time. He wrote many stories – I took notes of stories about the characters there. He had an idea of making a story about the people there.’

One of his hosts was D. L. James, who lived in a Spanish-style mansion perched on the cliff-edge in Carmel, one of northern California’s architectural monuments. (James’ parents actually had him baptized ‘D.L.’ with the idea that he could choose names to suit the initials when he grew up. In fact, he remained simply ‘D.L.’ though occasionally he intimated that he might consider ‘Dan’ as a first name.) At the James house Chaplin met D.L.’s son Dan, who was then twenty-six, an aspiring writer and ardent Marxist, who was at the time rather unsettled; “My writing was getting nowhere; I was separating from my wife; and I was just then thinking of going to New York.’ They met on several occasions and Dan would hold forth on films and about the war against Fascism. Chaplin in turn outlined his ideas for a Hitler film.

When Chaplin returned from Pebble Beach to Hollywood at the end of the summer, Dan James took a chance and wrote to him saying that he was enthusiastic about the idea of the Hitler film, and would be very happy to be able to work on it in any capacity. ‘I went on packing my bags for the East, though.’ Somewhat to his surprise a telephone call came from the Chaplin studio a few days later, and he was invited to call and see Alf Reeves, Chaplin’s longtime studio manager. Reeves warned him that Chaplin was very ‘changeable,’ but that he liked him and was prepared to employ him at a salary of $80 a week, and to put him up at the Beverly Hills Hotel until he could find somewhere to live. ‘My first evening he took me to Ciro’s Trocadero Oyster bar; then we dined and he told me the outline of the story. The next day I went up and started to make notes . . . I think Charlie took me on because of my height, because my family had a castle out here, and because he knew pretty quickly I was a declared Communist, so that my background and political preoccupations would keep me from selling him out for money.’

For three months James reported daily to Chaplin’s Beverly Hills mansion – known as “Breakaway House” – where he would make notes as Chaplin discussed ideas for the plot and gags. From time to time James would go to the studio to dictate the notes to Kathleen Prior: the first of these dictation sessions seems to have taken place on October 26, 1938. During these three months James was able to assess Chaplin’s own political thinking:

He did not read deeply, but he felt deeply everything that happened. The end of Modern Times, for instance, reflected perfectly the optimism of the New Deal period; already by 1934 and 1935 he had a sense of that. He had probably never read Marx, but his conception of the millionaire in City Lights is an exact image for Marx’s conception of the business cycle. Marx wrote of the madness of the business cycle once it began to roll, the veering from one extreme to another. Chaplin presents a magnificent metaphor. Whether he was aware of the social meaning of this I do not know, but he got it.

He had a sixth sense about a lot of things. In 1927 and 1928, for instance, he began to feel that the stock market was going mad, and he took everything he had and put it into Canadian gold.

Charlie called himself an anarchist. He was always fascinated with people of the left. One of the people he wanted to meet was Harry Bridges of the Longshoremen’s Union. I fixed up a meeting, and they took to each other immediately.

Whatever his exact politics, Charlie had a position of revolt against wealth and stuffiness. He had a real feeling for the underdog. He was certainly a libertarian. He saw Stalin as a dangerous dictator very early, and I had great difficulty getting him to leave Stalin out of the last speech in The Great Dictator. He was horrified by the Soviet-German Pact.

When it came to Hitler it is easy to say, with hindsight, that Chaplin made too light of him. You have to remember that the film was conceived before Munich, and that Chaplin had undoubtedly had it in his head a couple of years before that. And the thought then was that this monster was not so awe-inspiring as he appeared. He was a big phony, and had to be shown up as such. Of course, by the time the film appeared, France had fallen and we knew much more, so that a lot of the comedy had lost its point.

The Great Dictator marked an inevitable revolution in Chaplin’s working methods. This was to be his first dialogue film, and for the first time he was to begin a picture with a complete script. The old method had been to work out each sequence in turn, alternating periods of story preparation with shooting – changing, selecting and discarding ideas as the work proceeded. Now these processes had to be transferred to the preparatory period, the work of a definitive script.

The original and basic premise was the physical resemblance of the Dictator and the little Jew. All the early treatments of the story begin with the return of Jewish soldiers, many maimed, from the war to the ghetto. They are all welcomed back by wives and families, except ‘the little Jew.’ He ‘is alone walking down the ghetto street. In his hunger for companionship he embraces a lamppost.’

One early idea was for a flophouse sequence which can be used for the setting of our inflation material. (This may have been suggested by D.W. Griffith’s Isn’t Life Wonderful) The little Jew will return to pay a bill. The sign will read, ‘Beds, $1,000,000 a night – baths $500,000 extra.’ Someone will send out for a package of cigarettes: ‘You’ll have to carry the money yourself,’ or perhaps the little Jew goes out balancing a huge basket of currency on his head. $10,000,000 for cigars. The tobacco dealer insists that the money be counted. It is all in $1.00 bills.

Never willing to waste a good comedy idea, Chaplin planned to use a flea circus routine . . . something he had been toying with for more than a quarter century. It stayed in through several successive treatments, but was finally abandoned. Having been frustrated in his efforts to introduce the business into his 1928 picture The Circus, and The Great Dictator, Chaplin would eventually manage to squeeze it into Limelight in 1952.

Chaplin early conceived the idea of two rival dictators competing to upstage one another. He was to abandon an idea for the Great Dictator’s wife, a role intended for the famous Jewish comedian Fanny Brice. A scene was sketched out, with a lot of revision in Dan James’ handwriting, indicating the kind of relationship Chaplin had in mind, and suggests that it might have encountered serious problems with the Breen Office and other censorship groups:

SCENE: Mrs. Hinkle alone – boredom and sex starvation with Freudian fruit symbols. Enter Hinkle from speech. She’s mad at him – orders him about. He’s preoccupied about matters of State.

Mrs: I’m a woman. I need affection, and all you think about is the State! THE STATE! What kind of state do you think I’m in?

Hinkle: You’ve made me come to myself. I’m not getting any younger. Sometimes I wonder . . .

Mrs: Life is so short and these moments are so rare . . . Remember, Hinkle, I did everything for you. I even had an operation . . . on my nose. If you don’t pay more attention to me I’ll tell the whole world I’m Jewish!

Hinkle: Shhh!

Fanny: And I’m not so sure you aren’t Jewish too. We’re having gefilte fish for dinner.

Hinkle: Quiet! Quiet!

Fanny: Last night I dreamt about blimps . . .

Hinkle: Blimps?

Fanny: Yes, I dreamt we captured Paris in a big blimp and we went right through the Arc de Triomphe. And then I dreamed about a city full of Washington monuments.

(She presses grapes in his mouth, plays with a banana.

By December 13, 1938, Chaplin had decided on much of the story, including the idea of the ending. Charlie and the father of the Girl from the ghetto with whom he has fallen in love are put in a concentration camp. They escape, and on the road run into Hinkle’s troops, preparing to invade the neighboring country of Ostrich (which would, in the final cut, become Osterlich, the real last name [although spelled differently] of Fred Astaire). The general in command mistakes Charlie for Hinkle. Hinkle himself, out shooting ducks while trying to make up his mind about the invasion, is meanwhile mistaken for Charlie and thrown into prison.

Charlie and the Girl’s father are carried along on the invasion of Ostrich and finally find themselves in the palace square of Vanilla, the capital.

Hinkle’s soldiers are drawn up before the platform from which the conqueror is about to speak. Charlie walks out on it. He can’t say a word. The Girl’s father is at his shoulder. ‘You’ve got to talk now! It’s our only chance! For G-d’s sake, say something.’ Herring (Hinkle’s P.M.) first addresses the crown – and through microphones the whole world, which is listening in, he calls for an end to democracies. He introduces Hinkle, the new conqueror, who must be obeyed or else. In the crowd we show dozens of Ostrich patriots ready to kill Hinkle. Charlie steps forward. He begins – slowly – scared to death. But his words give him power. As he goes on, the clown turns into the prophet. [The following video capture - long known as the “Look Up Hannah speech” - is, in my humble opinion, great bit of writing and acting in the history of motion pictures.)

By the middle of January 1939 Chaplin clearly felt confident with his story, though it was to undergo much subsequent revision. Dan James was set to adapt it into a dramatic composition in five acts and an epilogue, in order to register it for copyright. Copyright was also sought in the title The Dictator, but it was discovered that Paramount Pictures and the estate of Richard Harding Davies already owned the title and were unwilling to relinquish it. In June, therefore, the title The Great Dictator was registered, but Chaplin was not entirely convinced that it was right; having already registered Ptomania, he subsequently registered as alternatives The Two Dictators, Dictamania and Dictator of Ptomania.

The Chaplin Studio c. 1917

After January 16, Dan James no longer went to the Beverly Hills house, since Chaplin now worked at the studio, where he could supervise preparations for shooting. The stage was being soundproofed; there were contracts to be negotiated with outside organizations like RCA who were to be responsible for the sound; and work was already in hand on miniatures for special effects. Now the daily script conferences took place in Chaplin’s bungalow on the lot. On January 21, Charlie’s brother Sidney returned to work at the studio for the first time in almost 20 years; with conditions in Europe as they were, he and his new French wife, Gypsy, had decided that they were likely to be safer in America. The daily script conferences were now augmented, as Sydney and Henry Bergman (who had been with Charlie ever since the beginning of his film career at the Sennett Studios) joined Chaplin and Dan James.

By the late summer of 1939 when the script was finished and Chaplin was ready to start shooting, he was able to reassure Sydney: “This time, Syd, I have the script totally visualized. I know where every close-up comes.” Of course, it didn’t quite work out that way. It rarely ever does . . . especially with a filmmaker like Chaplin.

During the weeks of preparation, Chaplin ran films for his staff in the studio projection room, among them Shoulder Arms and the mysterious The Professor - a likely unfinished and definitely unreleased Chaplin film from c. 1919). He also screened all the newsreels of Hitler on which he could lay hands. He later returned often to a particular sequence showing Hitler at the signing of the French surrender. As Hitler left the railway carriage, he seemed to do a little dance. Chaplin would watch the scene with fascination, exclaiming, “Oh, you bastard, you son-of-a-bitch swine. I know what’s in your mind.” According to Tim Durant, “He said, ‘this guy is one of the greatest actors I’ve ever seen’ . . . Charlie admired his acting. He really did.” Dan James commented nearly a half-century later, “Of course he had in himself some of the qualities that Hitler had. He dominated his world. He created his world. And Chaplin’s world was not a democracy either. Charlie was the dictator of all those things.”

The script, which was completed by September 1, 1939, remains one of the most elaborate ever made for a Hollywood film. It runs to the extraordinary length of almost 300 pages (the average feature film script varies from 100 to 150 pages). It was divided into twenty-five sections, each designated by a letter of the alphabet and separately paginated; through shooting every take was identified by the letter and number of the relevant script page. Despite the doubt Dan James cast on Chaplin’s assertion that everything was visualized, the system seems, to judge from the shooting records, to have served pretty well in the 168 days of a very complicated production.

Throughout the spring and early summer of 1939 Chaplin was collecting his crew around him. Henry Bergman was nominated “co-ordinator.” Dan James was joined by two more assistant directors. One was Chaplin’s half-brother Wheeler Dryden, who arrived at the La Brea Blvd. studio in March, overjoyed to be given a job on Chaplin’s permanent studio staff. Wheeler had continued to pick up a living as an actor and in 1923 had had a play, Suspicion, produced at the Egan Theatre in Los Angeles. He was to remain at the studio until Chaplin’s departure from the United States in 1952. A slight man, Wheeler retained the air and diction of an old-style stage actor. Though he adored Charlie, Wheeler could sometimes madden him as well as the rest of the studio staff with his finicky attention to detail.

The amusing and devil-may-care Robert Meltzer, another assistant director, like James an avowed Communist, was in striking contrast to the solemn and nervy Wheeler. He had also been recruited in Pebble Beach. During the summer there the gossip writers had linked Chaplain’s name with several women, notably the sugar heiress Geraldine Spreckels and a striking young red-headed actress named Dorothy Comingore, whom Chaplin saw on stage in Carmel. Comingore was then living with Bob Meltzer, and when Chaplin convinced her that she should try her luck in Los Angles, Meltzer came too. In the end it was Meltzer who worked for Chaplin and not Miss Comingore, who joined Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre and made her most striking impact as Susan Alexander – the role transparently based on Marion Davies – in Citizen Kane. After The Great Dictator Meltzer himself was to work briefly with Welles. With the outbreak of hostilities in 1941 he volunteered for service with the paratroops and died in the Battle of Normandy at age 31.

Chaplin’s staff was astonished when Chaplin engaged Karl Struss as director of photography. After 23 years as Chaplin’s senior cameraman this was a cruel blow to Rollie Totheroh, who could never afterwards completely forgive his beloved boss. Chaplin had grown dissatisfied with Rollie’s camerawork for reasons which were never quite clear.

Part of the problem for a director making only one film every four or five years was that in the interval conditions in Hollywood had changed. Each time Chaplin made a film he found himself bedeviled by new technical people whom he neither understood nor needed. He had a running feud with the script girl – a personage hitherto unknown on a Chaplin film.

The role of Hannah was all along intended for Paulette Goddard, who reported for work at the studio on July 29. She and Chaplin had spent a good deal of the previous year apart. While he went to Pebble Beach in the early half of 1938, she flew to Florida, and during most of the rest of the year she was at work in Hollywood, while he stayed away from the studio. Already in March, while hardly finished with marriage rumours, the newspapers talked of impending divorce. Paulette’s contract with the studio expired on March 31, 1938, and she had sought an earlier release to sign with the Myron Selznick agency. She was hired for The Great Dictator at $2,500 a week; Chaplin was furious when she brought her agent (probably Selznick himself) to demand bigger billing.

She and Chaplin continued to live together in the Summit Drive mansion throughout the production of the film. As Chaplin nicely expressed it, ‘Although we were somewhat estranged we were friends and still married.’ To the Chaplin sons, now mischievous early teenagers, and to casual acquaintances, their relationship seemed much as before. At the studio, the staff were however aware of the change. You either belonged to the Paulette faction or to the Charlie faction. You couldn’t be both. Chaplin would work very hard with her; sometimes he would make twenty-five or thirty takes. He would stand in her place on the set and try and give her the tone and the gestures. It was a method he had been able to use in silent films; it could not work so well, of course, in a talking picture.

The final stenciled copies of the script were completed on Sunday September 3, 1939 – the day that Britain declared war on Germany. Three days later Chaplin began to rehearse and on September 9 shooting began on the first ghetto sequence. Filming was to continue with hardly a day’s break apart from (most weeks) Sundays until the end of March 1940. By that time Chaplin would have shot most of the 477,440 feet of film which were eventually to be exposed. The length of the finished picture was 11,625 feet.

It is interesting, but perhaps not too surprising, to discover that Chaplin kept the shooting of his two roles quite distinct. First, until the end of October, he worked on the scenes of the ghetto, in the character of the barber. With the bulk of those completed, November was spent on the more complicated action and location scenes, like the war scenes, particularly those involving Reginald Gardiner and the crashed plane. Chaplin had devised some very funny business with the airplane. Taking over the controls, Chaplin manages to turn it upside down without either himself or his companion (Gardiner) being aware of it. They only notice with some concern that the sun is shining up from below them, that a watch released from a pocket leaps (apparently) into the air and sways there on its taut chain, and that they are passed by flocks of upside-down seagulls. Reginald Gardiner suffered much more than Chaplin from the experience of being strapped upside down, and only managed his lines and air of insouciance with great difficulty.

There were interludes and distractions in the work at the studio that November. Not all were welcome: a plagiarism suit brought by writer Michael Kustoff on account of Modern Times came to trial in federal court and kept both Chaplin and studio manager Alf Reeves busy. Chaplin himself was in court on November 18 when the case was decided in his favor.

On November 15, 1939 Douglas Fairbanks and his new wife, Sylvia, the former lady Ashley, visited the location in Laurel Canyon where Chaplin was filming. Chaplin thought he looked older and stouter, though he was still as full of enthusiasm. He had always been Chaplin’s favorite audience, and as so many times before, Chaplin showed Fairbanks his sets and expounded his plans. Although he was filming in the Barber’s concentration camp costume, Chaplin put on his Hynkel uniform to show his visitors, and wearing it, was photographed with them. They all lunched together.

Chaplin & Fairbanks: the final photo

It was the last time he saw the man whom he later said had been his only close friend. At four o’clock in the morning of December 12, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. telephoned Chaplin to tell him that his father had died just over three hours earlier, in his sleep. There was no shooting at the Chaplin studio on the day of his funeral, December 15. “It was a terrible shock,” Chaplin later wrote, “for he belonged so much to life . . . I have missed his delightful friendship.”

As December came, Chaplin began his Hynkel scenes. The supreme actor, Chaplin always became totally subsumed into the role he was playing, as colleagues throughout his career have testified. When, for the first time, he adopted the uniform and role of an autocratic and villainous character, even he was momentarily disconcerted by the effect. Reginald Gardiner remembered that when Chaplin first appeared on the set ready to shoot in his Hynkel uniform, he was noticeably more cool and abrupt than when he had been playing the Jewish barber. Gardiner recalled further that when he was driving with Chaplin – already in uniform – to a new location, Chaplin suddenly became uncharacteristically abusive towards the driver of a car that was obstructing them. He quickly recovered himself, and recalled with laughter an earlier discussion about the false sense of superiority a uniform can produce. ‘Just because I’m dressed up in this darned thing I go and do a thing like that.’

Although work on The Great Dictator proceeded on a much tighter schedule and pre-set plan than any previous Chaplin film, there was no fixed daily routine in the studio. Much, of course, depended upon Chaplin’s own somewhat unpredictable time of arrival, although for the first time he appears to have delegated considerable responsibility for preparation and in some cases shooting to his assistants.

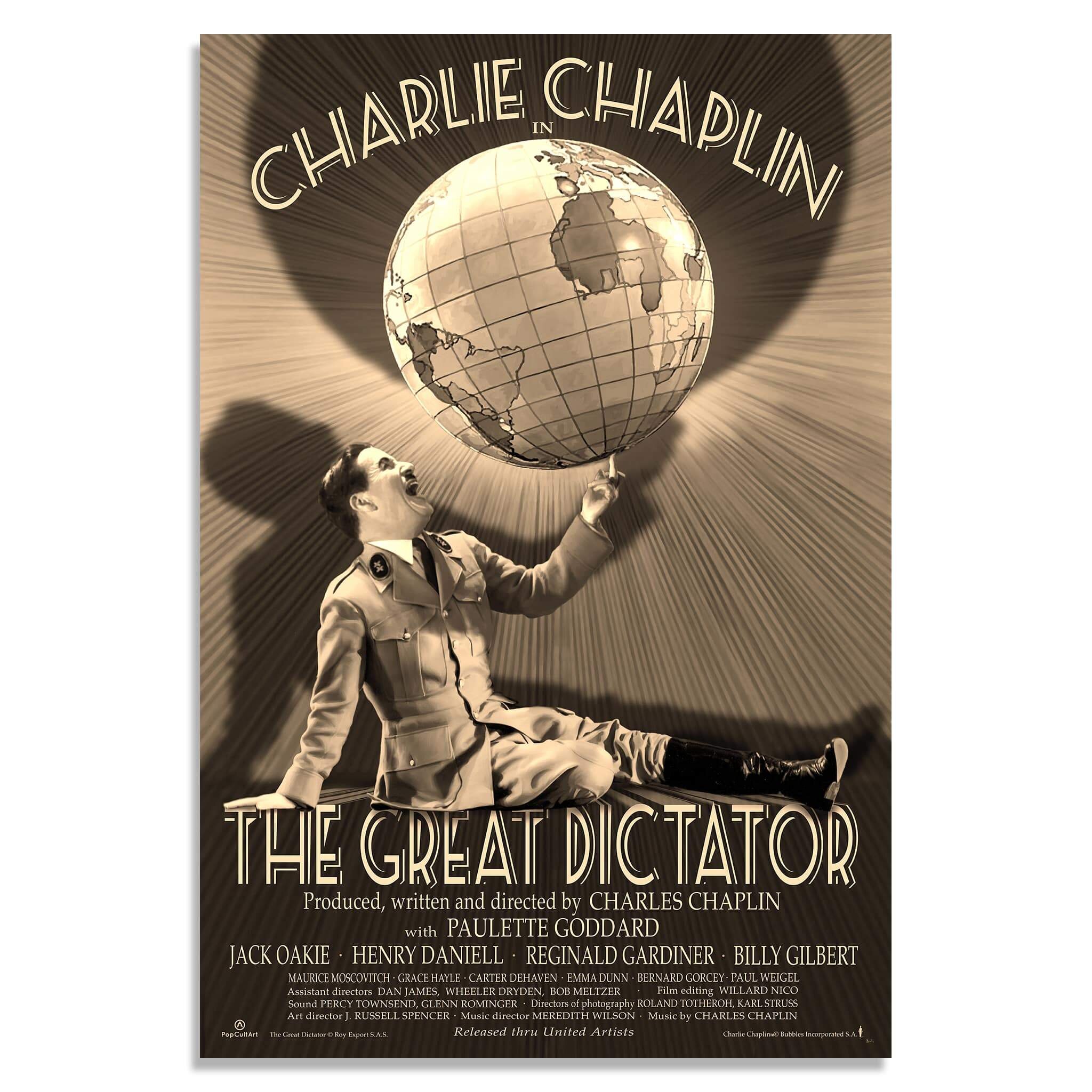

Just before Christmas, Chaplin shot the scene which remains the most haunting and the most inspired of the film: Hynkel’s ballet with the terrestrial globe. The first hint of a symbolic scene of this sort is a random story note dating from February 15, 1939:

SCENE WITH MAP: Cutting it up to suit himself, cutting off bits of countries with a pair of scissors.

The dance with the globe was to go far beyond this elementary notion. While the gibberish speech appears so precise and planned that it is surprising to discover that it was improvised, the dance with the globe seems to soar so freely in its inspiration that it is hard to imagine that it could be written down. Yet it was. In the complete version of the script, the description of Chaplin pas seul occupies four pages, opening,

HYNKEL GOES TO THE GLOBE – and caresses it – trance-like. Soft strains of Peer Gynt (in the outcome the Prelude to Lohengrin proved more appropriate) waft into the room. Hynkel picks up the globe, bumps it into the air with his left wrist. It floats like a balloon and drops back into his hands. He bumps it with his right wrist and catches it. He dominates the world – kicks it viciously away. Sees himself in the mirror – plays God! Beckons, the world float into his hand. Then he bumps it high in the air with his right wrist. He leaps up (on wire), catches the globe and brings it down.

The particular attention that Chaplin was to give to the balloon dance indicates that he was well aware that it would remain one of his great virtuoso scenes. He spent three days on the main shooting in the days just before Christmas, and then made some retakes in early January. The first three days in February seem to have been entirely taken up with running and rerunning the material, and on February 6 and again of the 15th Chaplin did further retakes.

Carter De Haven, who plays the Bacterian Ambassador in the film, was later to attempt to get into the plagiarism game by claiming the ballet with the globe was his idea. Any doubt, however, was finally put to rest when Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, preparing their Unknown Chaplin film series, unearthed some forgotten home movies (39) of a party at Pickfair in the early 1920s. Chaplin, in classical Grecian costume and crowned with a laurel wreath, performs a dance with a balloon which is the unmistakable prototype for The Great Dictator. No doubt Chaplin was remembering his party trick of nearly twenty years ago when he noted in the script description of the globe ballet, ‘Then he slides to the table top to perform a series of Greek postures’ and ‘Gracefully he leans back over the desk and gets very Greek about the whole thing.’

In January 1940 Jack Oakie joined the cast to play Benzino Napaloni, the Dictator of Bacteria. When Chaplin first proposed the role to him, Oakie questioned the suitability of casting an Irish-Scottish American in a caricature of Mussolini. What, asked Chaplin, would be funny about an Italian playing Mussolini? Chaplin did perceive a problem however when he discovered that Oakie was at the time dieting to lose weight. According to Charles Chaplin Jr., his father brought his own cook, George, to the studio and had him tempt Oakie with the richest and most fattening dishes he could devise. When he found his strategy was succeeding, and that Oakie was increasingly growing to resemble Mussolini in stature, he cheerfully nicknamed him ‘Muscles.’

Charles Junior considered that ‘one of the pleasantest things about the new film was the affable relationship between Dad and Jack Oakie. Jack had a tough hide and was able to take Dad’s drive in stride. Dad, on his part, has always had great admiration for Jack.’ Others on the set observed that working in his scenes with Oakie brought out a certain competitive spirit in Chaplin It was not jealousy: rationally, Chaplin knew that his supremacy was unassailable. Rather it was Chaplin’s legacy from his early training with Karno and Keystone: the essential and driving motive for a comedian must always be to outdo the rest. Chaplin’s own script for The Great Dictator often gave the better comedy business to Oakie. Chaplain’s professional instinct still drove him to top it with his own comedy. He would sense the reaction of the unit, and he played the comic game with the same intensity as he played tennis. As with tennis, he did not like to lose: finishing a scene in which he felt that Oakie had scored the biggest laughs from the bystanders, he could hardly conceal his irritation. Charles Junior, a very reliable witness, despite his youth at the time, recalled one day when Oakie had tried every trick he knew to do the impossible and steal a scene from Chaplin. In the middle of the scene, Chaplin grinned and offered advice: “If you really want to steal a scene from me, you son-of-a-bitch, just look straight into the camera. That’ll do it every time.”

Chaplin undoubtedly found these duels of comedy nostalgic and stimulating. He was less happy with some of his actors from the legitimate theatre. In particular he found it very hard to work against Henry Daniell’s measured timing. “He developed a hatred for Daniell,” recalled Dan James. “He really thought Daniell was trying to sabotage him. The trouble was that he had a respect for Daniell because he was a real stage actor, and couldn’t bring himself to explain what was wrong. Poor Daniell knew that Chaplin was not pleased with him, but he never understood why. On the other hand he was crazy about Reggie Gardiner, though once he had got him, he never really gave Reggie any funny stuff.

By the middle of February practically all the studio scenes had been shot. Chaplin moved out onto location to shoot the First World War scenes for the opening of the film and the scene of Hynkel being arrested while out duck shooting, filmed at Malibu Lake. The war scenes involved a series of gags with Chaplin and the enormous Big Bertha gun, and for one day’s shooting the Chaplin children were taken to watch. Fourteen-year-old Sydney was so overcome with mirth at his father’s antics following the explosion of the gun that he laughed out loud. When he discovered who had wrecked the sound take, Chaplin flew at him in fury, saying ‘Do you know your laugh just cost me fifteen thousand dollars?’

‘In a twinkling, from being the funniest man alive, Dad had become the most furious.’ The two boys feared some awful retribution; but then Chaplin began to laugh, and proudly called out to the crew, ‘Even my own son thinks I’m funny.’ To Sydney he added, ‘Well, it was fifteen thousand dollars’ worth of laugh, but if you appreciated it that much, it’s all right . . . Just don’t let it happen again, son.”

One series of scenes shot during this period was destined never to be seen. Chaplin’s first idea for the final scene of the speech, in which (in the words of the early treatment) ‘the clown turns into a prophet’ was extremely ambitious. He intended the speech to be laid over scenes supposed to take place in Spain, China, a German street and a Jewish ghetto in Germany. As Chaplin’s speech came into heir consciousness, a Spanish firing squad would throw down their arms; a Japanese bomber pilot would be overcome by wonder, and instead of bombs, toys on parachutes would rain down on the Chinese children below; a parade of goose-stepping German soldiers would break into waltz-time; and a Nazi storm-trooper would risk his life to save a little Jewish girl from an oncoming car. A couple of days were actually spent shooting material for the sequence, but it was discarded.

By the end of March 1940, the main shooting was all finished, the laborers were already beginning to clear the studio, and Chaplin had a rough-cut of the film ready to show to a few friends such as Constance Collier in early April. The climactic scene, the final speech made by the little barber who has been mistaken for the Great Dictator, remained to be shot. Moreover Chaplin was to polish and tinker with the film more than with any other that he had ever made. During the next six months he would suddenly decide to put up a set again; and he was still doing retakes of the ghetto scenes in late September, after he had already previewed the film. Redubbing of the sound went on practically until the premiere on October 15, 1940.

From April to June Chaplin labored over the text of his big speech, between working on the editing of the film. His two young Marxist assistants were of no help to him. The Utopian idealism and unashamed emotionalism of the speech evidently offended their Communist orthodoxy. Others were anxious about the speech on more pragmatic grounds. When told by his film salesmen that the speech might lose him a million dollars in sales, Chaplin reportedly said, “I don’t care if it loses me $5 million . . . it’s my money, and it’s worth it.

That final speech, which the political right felt smacked of Communism and the left suspected of sentimentality, seemed not to embarrass the larger audience. It was widely quoted and reprinted. Chaplin’s old friend Rob Wagner devoted a page to it in the November 16 issue of his magazine Rob Wagner’s Script; Archie Mayo, mainly remembered as the director of The Petrified Forest, used it as his Christmas card for 1940, comparing it to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address; and in England, the Communist Party put it out as a special pamphlet.

The Great Dictator was nominated for 5 Oscars, including best actor, best supporting actor, best screenplay and best original music for Meredith Wilson. Although it did win the New York Film Critics Award for Picture of the Year, Chaplin refused to accept it. It wound up being his most profitable picture, earning him slightly more than $5 million. It is also one of the first films named to the National Film Registry.

Throughout his career, people assumed that Chaplin was Jewish. After all, he was probably a Communist (so they believed) and weren’t a majority of Hollywood Reds Jewish? Throughout most of his life, Chaplin did not address the issue. Towards the end, however, a writer posed the question for perhaps the thousandth time. Chaplin’s response?

“I’ve never had that honor.”

Enjoy the film . . .